Implementing fast TCP fingerprinting with eBPF

In this article I want to document my journey implementing fast TCP fingerprinting in a golang webserver, using eBPF.

Just to provide some background, TCP fingerprinting is one of the many techniques that can be used to detect

unusual or identifying informations about a web request when implementing an anti-bot solution.

This has been a hot topic lately, caused by the rising need to scrape the internet for human content to feeed to the LLMs.

Implementing such a system offers interesting technical challenges that span different domains,

but most importantly it’s a very good first project to learn eBPF.

I split this article in two parts.

- In this first part I provide a background on TCP fingerprinting, and discuss some implementation strategies.

- In the second part I describe the actual development of a proof-of-concept Golang webserver that echoes back the TCP fingerprint of the client. The project is open source on Github

HTTP requests, from first principles

It can be useful to approach this problem from first principles, looking at the way web servers work under the hood.

This is not as scary as it might seem: although browsers and the underlying protocols evolved and got more complex over time, for compatibility reasons they still support the HTTP/1.0 protocol, which was designed to be simple. An HTTP/1.0 web server is just a light layer on top of a TCP connection, and can be implemented in just a few lines of C code.

As an example, I implemented a simple hello world webserver in C that we’ll use as a starting point for the experiments in this article. You don’t really have to read the code for now, but keep in mind that it’s here:

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define PORT 8080

int main() {

// Create socket file descriptor

int server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (server_fd == 0) {

perror("socket failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Create a configuration struct with the network address and port

struct sockaddr_in address = {

.sin_family = AF_INET,

.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY,

.sin_port = htons(PORT)

};

socklen_t address_length = sizeof(address);

struct sockaddr *address_pointer = (struct sockaddr *)&address;

// Bind the socket to the network address and port

if (bind(server_fd, address_pointer, address_length) < 0) {

perror("bind failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Listen for connections

if (listen(server_fd, 1) < 0) {

perror("listen failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("Server listening on port %d...\n", PORT);

while (1) {

// Accept a new connection

int new_socket = accept(server_fd, address_pointer, &address_length);

if (new_socket < 0) {

perror("accept failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Send a response

const char *response = "HTTP/1.0 200 OK\r\n"

"Content-Type: text/plain\r\n"

"Content-Length: 12\r\n"

"\r\n"

"Hello world ";

send(new_socket, response, strlen(response), 0);

// Close the connection

close(new_socket);

}

return 0;

}

This is certainly not a production ready webserver, but it does its job.

If we compile the code, run it, and visit http://127.0.0.1:8080

from any modern browser, we’ll be greeted by a hello world:

Beautiful, isn’t it?

This code differs significantly from the hello worlds that you would normally write

with a modern web framework, regardles of what’s trending today, for an important reason:

We are directly using the abstraction layer provided by the operative system, nothing is

hidden away.

All the code in this example can be broken down into a few calls of the C standard library. Those functions are just thin wrappers around syscalls whith a similar name, which are all we need to implement a webserver on a POSIX system:

- we create a

socket - we

bindit to a ip and port, and start tolisten - in an infinite loop, we call

accept(), which blocks the execution until a client connects to our server - after a connection is made, accept returns a file descriptor

which we can

readandwriteto like a simple file. At the other end of the line, the client will communicate with us in a similar way.

It’s easy to see that beyond defining an ip and port we don’t

have to write any networking-related code, the OS is taking care of that for us.

Because of that, if we want to understand what’s happening at a deeper level we need to

capture and inspect the network traffic that reaches our webserver, which is something that

we can easily do with wireshark.

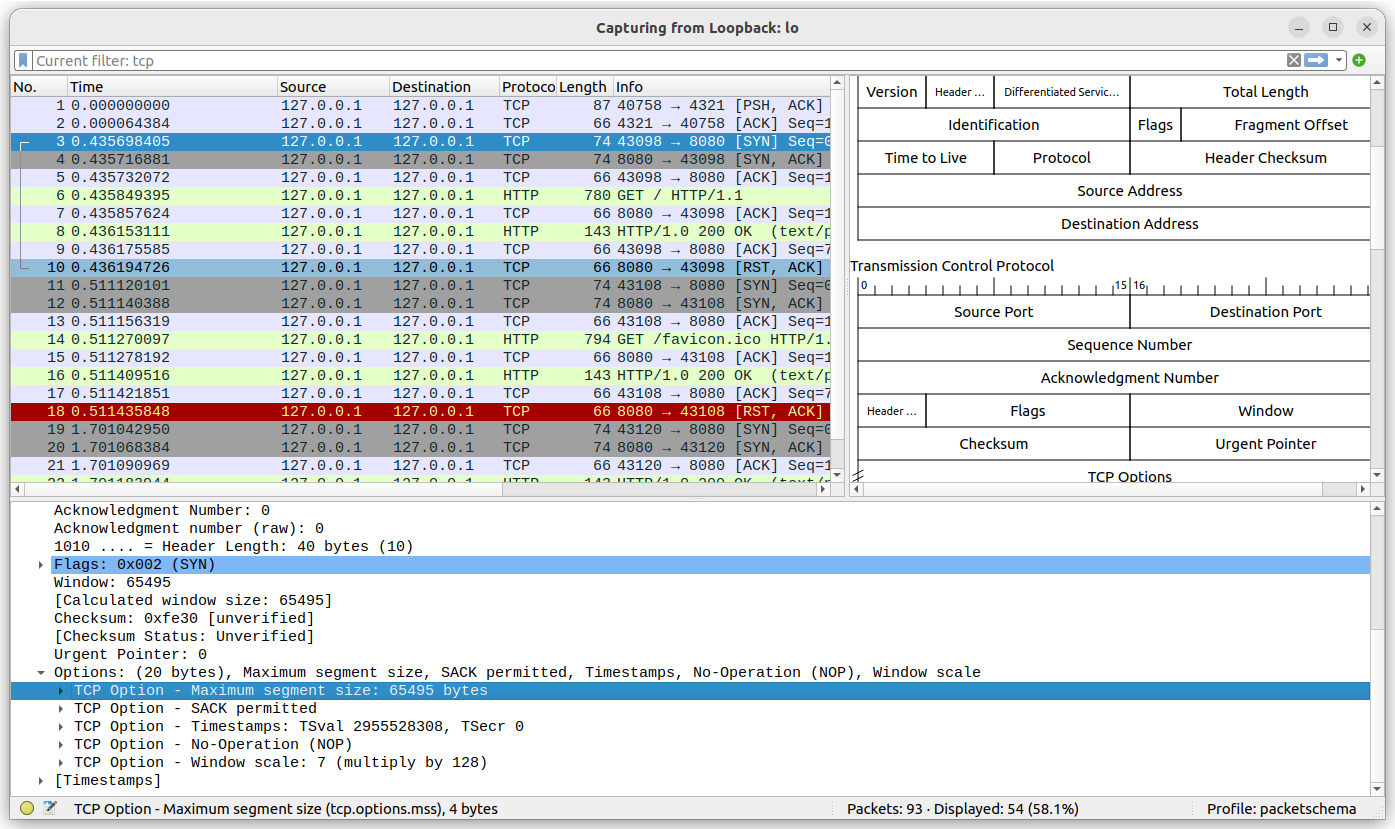

To capture the packets shown in this screenshot I launched wireshark on the loopback interface, then I visited the hello world website from the browser in order to generate some data.

With this webserver running and with our example traffic capture at hand, we can now start to experiment with tcp traffic.

Anatomy of a TCP handshake

TCP connections start with a famous three-way handhshake, During which both the client and the server exchange some informations that are useful to establish a reliable connection.

Historically, the informations exchanged during the handshake have always provided useful insight into the identity of the client.

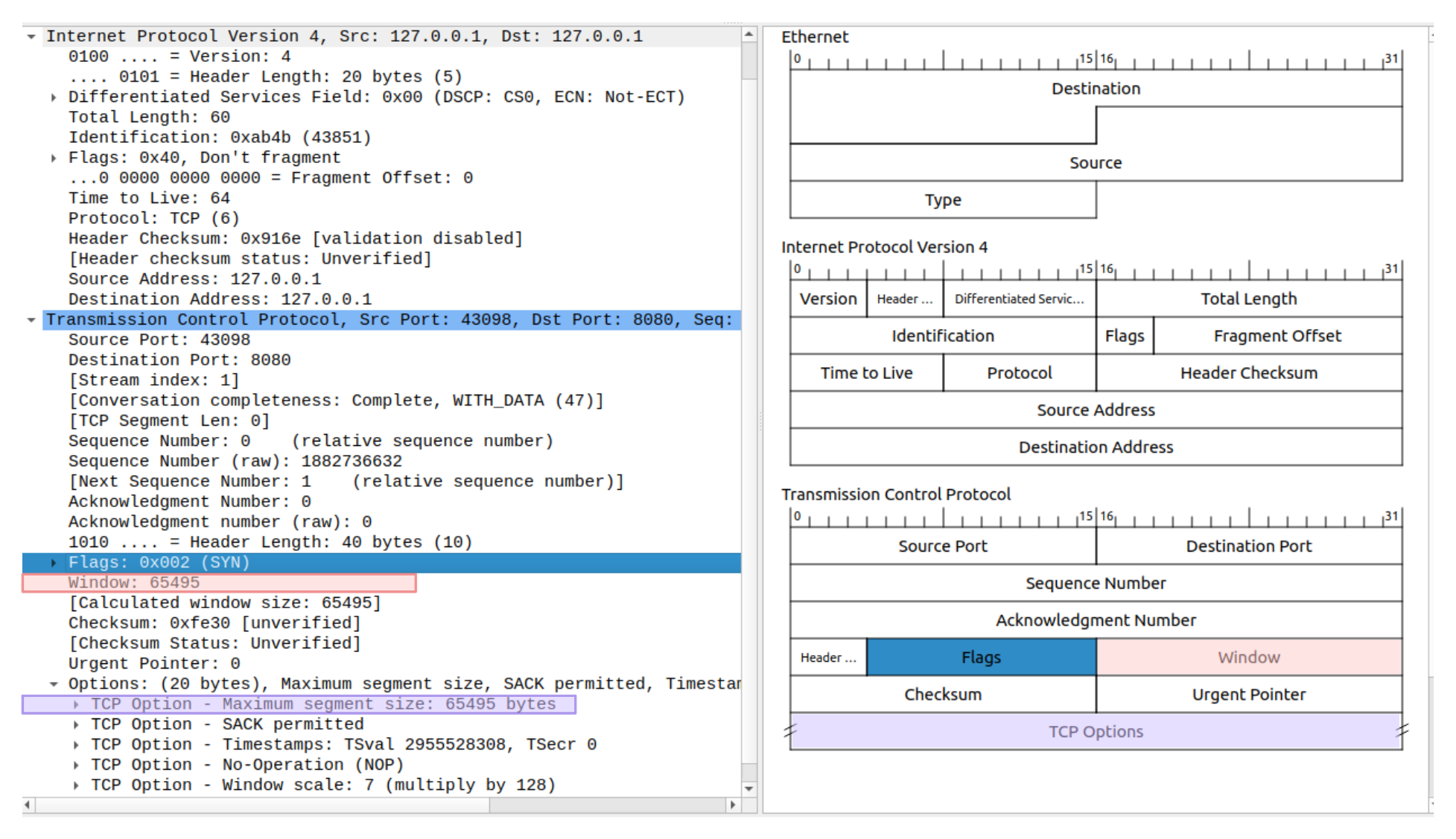

Let’s have a look at the first TCP SYN in my packet captures, to start with a concrete example:

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of informations we can gather from this data:

- informations about the Device that generated the packet

- informations about the route the packet travelled trough

A good overview of all these informations is provided by the authors of the ja4t TCP fingerprint, in an article I highly recommend. It’s not my intention to repeat what’s already been written extensively on the topic, so I’ll focus on only one of the TCP options, just to provide an example: the MSS.

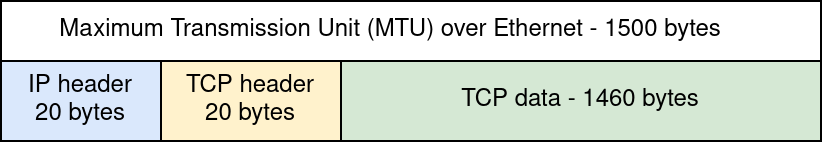

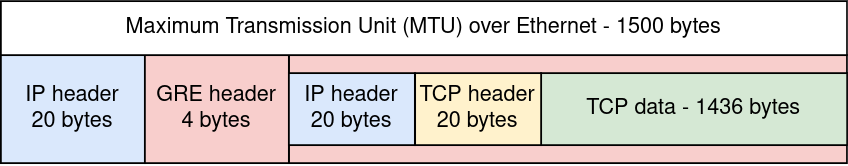

the Maximum Segment Size (MSS) TCP option can provide useful informations on the route of the packet.

In the packet we are analyzing, it’s the value

highlighted in purple.

This value represents the maximum size of TCP payload data that can be sent per packet,

and is dependent on the overhead in the network connection.

For example, over ethernet we usually cannot send more than 1500 bytes over a single transaction,

so the MSS will be 1500 minus the size of the TCP and IP headers.

Observing an mss of 1460 would indicate a standard connection over ethernet. a value smaller than that could be an indicator of several factors:

- The packet travelled trough a VPN service, GRE, IPsec, or any system that adds overhead to the transmitted backets.

- The user is on a mobile network

- any kind MSS clamping caused by middleboxes

Network connections can be complicated, and we can’t expect to learn everything from a single value. But at least it can provide some insight, and some entropy for a fingerprinting system.

Now, What about the MSS in the packet we are analyzing?

If you look carefully, you’ll see that the MSS is 65495,

way higher than what can fit in an Ethernet frame, and way off of

any value we talked about so far.

In a way, this is telling us something about the route too:

64Kb is the MTU of the loopback interface on Linux.

This data is telling us that the packet never left the kernel,

and lived in captivity without ever travelling the world.

TCP fingerprinting: Making a plan

Everything I talked about so far was just a big detour from the actual goal of this project,

which is to write a webserver that will echo back to the visitor

its TCP fingerprinting data.

For something like this to work, the webserver needs to directly

access the TCP SYN data of the connections it receives.

Is this something that we can do with the existing POSIX APIs we are using?

As it turns out, not really.

When our server accepts a new client connection, the accept() function returns

a new file descriptor.

We can use getsockopt on that file descriptor

to receive some useful informations on the ongoing connection:

getsockopt(sockfd, IPPROTO_TCP, TCP_INFO, &info, &len)

IPPROTO_TCP indicates that we are interested on the tcp-layer of the socket connection

TCP_INFO asks to receive information on the connection, causing the function to return a

tcp_info struct.

Sadly, if you have a quick look at the contents of that struct, you’ll see that it only contains

informations on the ongoing connection, nothing related to the original TCP SYN data.

There is a tcpi_rcv_mss value for example, but that’s the result of a negotiation,

not what the client originally sent.

That’s all we can get from the POSIX APIs.

LibPCAP

The POSIX APIs don’t provide easy access to TCP SYNs, but we can follow the same approach as wireshark, and just capture raw packets in a userspace buffer. We can do this very easily with the LibPCAP library, which offers out of the box a very simple system for filtering and capturing network packets.

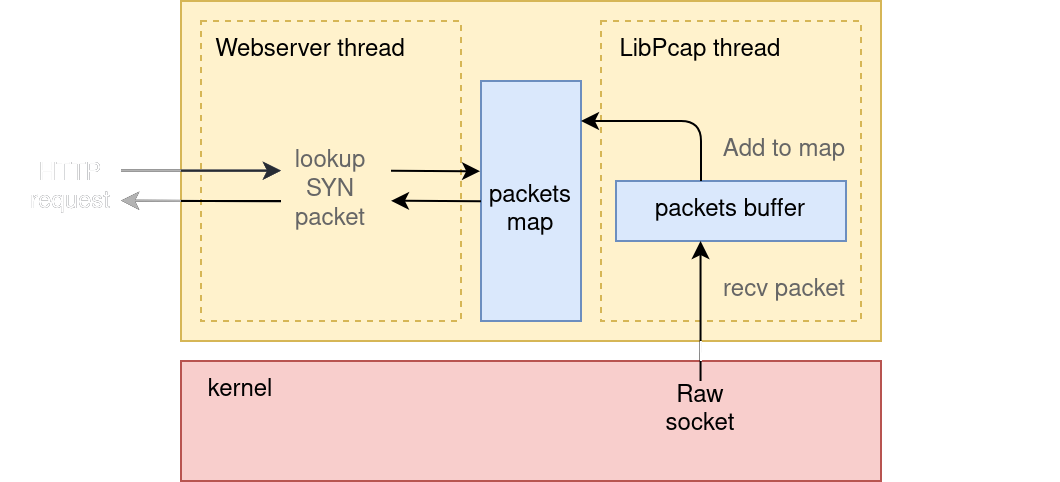

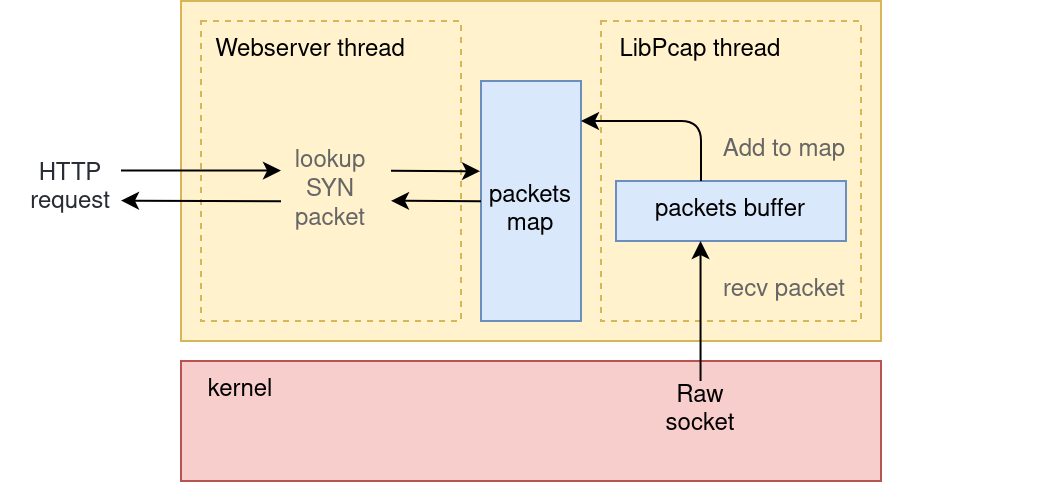

A simple approach to implement our webserver could work like this:

- First, we start LibPCAP in a separate thread, capturing TCP SYN packets that are directed to our webserver.

- When LibPCAP receives a packet, we store it in a hashmap with a key composed of

client IP + client PORT. - Then, when our webserver receives a request, we lookup the

client IP + client PORTtuple in the packets hashmap to find the right TCP SYN.

we are choosing that specific tuple for our lookup system because that’s how the TCP stack

uniquely identifies a connection in the kernel. To be more precise, it uses the tuple:

(client_ip, client_port, server_ip, server_port).

There are useful writeups on

socket lookups in the kernel that talk about this more in depth.

Sadly, there is a problem with this architecture:

- libpcap is not real-time.

When the server thread will

accept()a connection, it will try to lookup packet data that hasn’t been received yet. - even when receiving low-latency data from libpcap, copying and storing TCP packets into a hashmap is a slow operation.

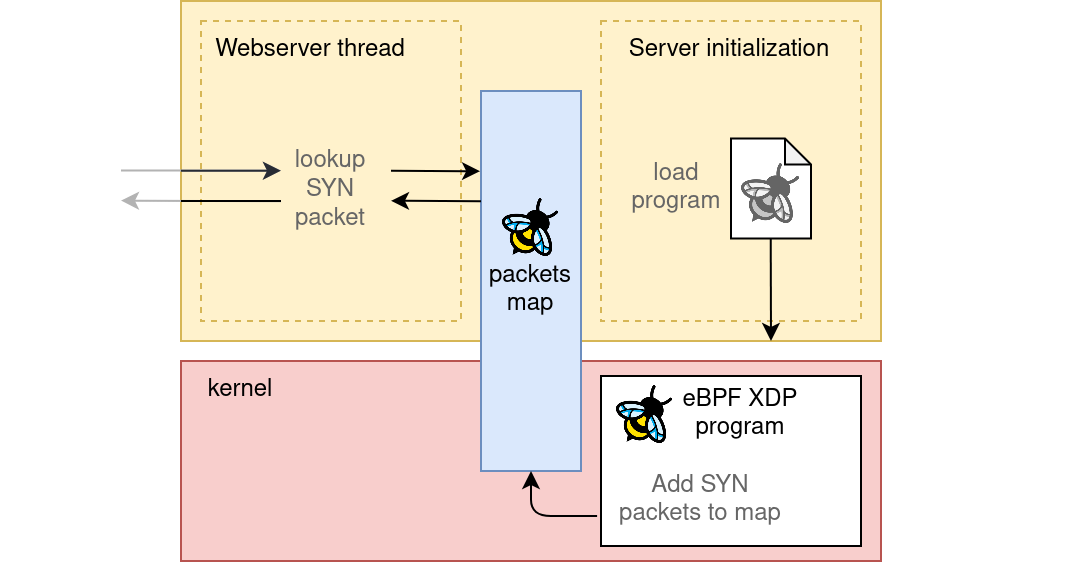

eBPF

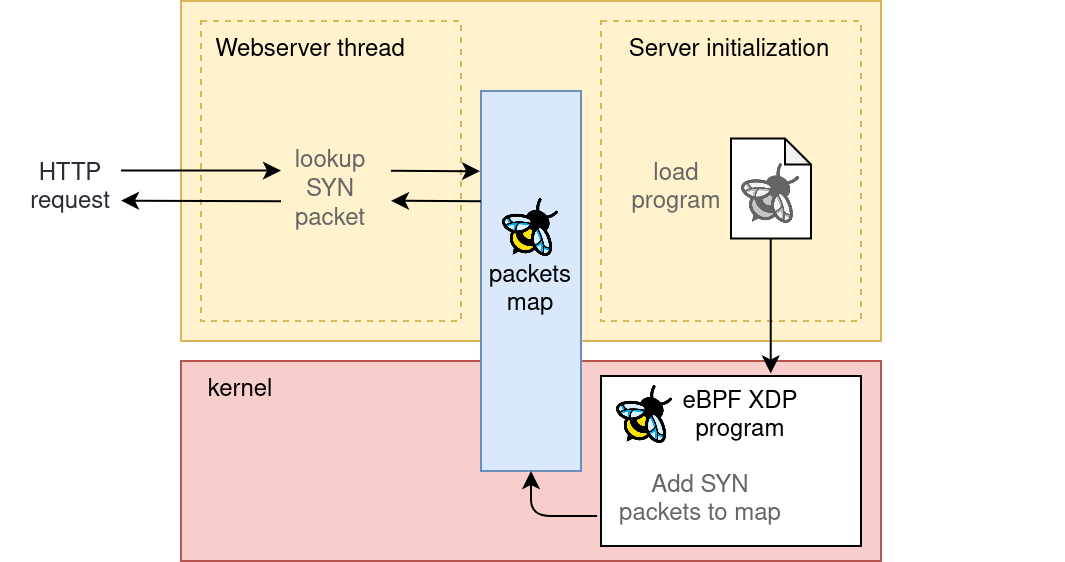

This is where eBPF comes to the resque. What if I told you that with eBPF we can generate that same hashmap of TCP SYN packets, but kernel side, without needing extra libraries and with little to no overhead on the system? The map will reside in kernel memory, but we’ll maintain the ability to query it from userspace, by simply referring to a file descriptor.

Compared to the previous diagram, this new architecture would simply replace the libpcap thread with an eBPF program running kernel-side.

Querying the map from userspace will require a single function call,

something along the lines of bpf_map_lookup_elem(map_reference, key).

All we’ll need to do first is initialize a custom eBPF program.

what is eBPF exactly?

The previous paragraph already provided a good introduction to what eBPF is, and what can be done with it: It’s a feature of the linux kernel, which introduces special event-driven programs that can run kernel side, and special data structures that both eBPF and user space programs can access and share.

This topic is very well documented, and has several introductory guides available. I recommend to check out

- ebpf.io

- the ebpf docs in the linux kernel

- the libbpf docs, and the libbpf bootstrap-demo repository in particular.

There are a lot of tooling and libraries that simplify the process of writing and executing eBPF programs. Since the end-result of this project needs to be in GO We’ll use the cilium eBPF library, wich provides an easy way to interact with an eBPF program drectly from GO, without dependencies on C or LibBpf.

The eBPF program we’ll need for our TCP SYN filter is particularly simple, so it happens to be

a very good first project to learn the topic in a practical way.

I documented the development of the program in the

second part of this article.